Imagine that you are a fast-food restaurant franchisee and that you operate and own 14 stores and the land they sit on. One day, you get a letter from your corporate partner, who just launched a new strategic initiative, asking you to remodel and update all 14 of your stores.

The total cost of the renovations is $2mm, which you do not have.

Unfortunately, based on your franchise agreement, you cannot push back on the corporate partner’s demands, or else you risk fines, penalties, or even the loss of your license.

Additionally, since you borrowed money to help you acquire new stores over time, the business already has a significant amount of debt on it, and you do not want to borrow more to pay for the renovations. What would you do?

One solution to finance the remodel is the topic of today’s post: “sale-leaseback”

Sale-leaseback Overview

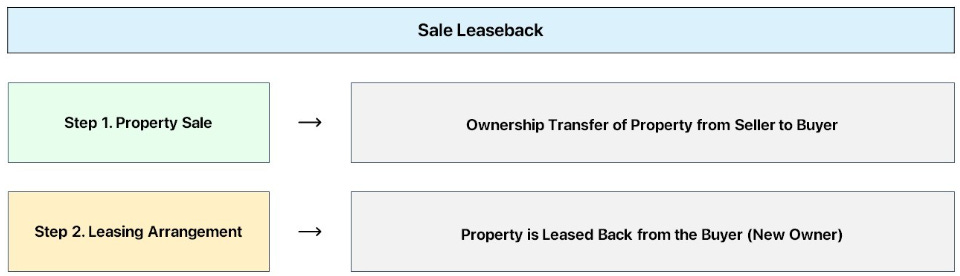

Let’s get to the post. A sale-leaseback is an arrangement in which a company sells an asset, which it then leases back from the purchaser. The details of this arrangement, such as the lease payments and lease duration, are made immediately after the sale of the asset.

While any high-cost, fixed assets–like equipment and machinery, fleet vehicles, and IT Infrastructure–can be used in a sale-leaseback, real estate holdings are typically the most common. Sale leasebacks have become increasingly common (and contentious) for several reasons that we will explore further in this article.

Source: SLB Capital Advisors, Wall Street Prep

In the case of the fast food franchisee example, you could sell your 14 physical buildings and land, either individually or at once, to a real estate investor for current market prices. You would then (effectively simultaneously) sign a series of long-term real estate leases with the acquiring real estate investor to lease the space back.

Let’s assume that the land was sold for $2mm in the transaction. Now, you can cover the total cost of renovations without needing to inject fresh capital into the business, or even worse, potentially needing to sell it due to a lack of liquidity. Now, not much will have changed operationally. You still own the franchise business and make money from it.

However, you do not own the land anymore and instead have to make the agreed-upon lease payments to your new landlord, the real estate investor who acquired your physical store buildings and land.

Structure of a sale-leaseback

The actual legal structure of a sale-leaseback is quite simple and includes two stages. In stage one, once an agreement is reached between both parties, the property is sold and ownership is transferred after the purchase is paid in full. The new owner assumes ownership of the property, including the option to commit to a new leasing agreement with the seller (former owner) right after closing.

In stage two, the new owner (now the lessor) and the prior owner agree to a new leasing agreement that permits the prior owner/seller (now the lessee) to remain in the space, but now as a tenant making lease payments. Typical base lease terms are 15-20 years, which are frequently combined with 5-10 year built-in renewal options. As a result, the lessee can be confident that they will be able to utilize the real estate for 40+ years.

Additionally, the lease may be structured as a triple net (NNN) lease, which commercial real estate investors prefer because it requires the lessee to bear expenses such as property taxes, building insurance, utilities, and maintenance.

Source: Wall Street Prep

Key Considerations and Unlocking Value

There are many reasons why a company might want to engage in a sale-leaseback. Some of the most common reasons are outlined below:

Deleveraging / Liquidity: sale-leasebacks are an effective tool for managing the balance sheet, in particular to reduce leverage or prevent a liquidity crunch (as seen in our fast-food franchise example). While rent expense is created, the reduction in leverage typically reduces both Debt / EBITDA and Debt / Total Capitalization.

Dividends / Buybacks: For publicly traded companies, executing a sale-leaseback and using the proceeds to buy back stock can potentially be accretive to earnings. Alternatively, for a private company, proceeds from a sale-leaseback can be immediately distributed to equity holders in the form of a dividend, a strategy used by private equity firms in an attempt to boost returns.

External Growth: Sale leasebacks are sometimes used by businesses to help fund M&A transactions, whether helping fund an add-on to an existing business (often used by private equity firms) or using proceeds in order to fund the acquisition of a new business

Redeployment of Capital to Higher ROI Opportunities: Given that real estate can be a low-return asset on the balance sheet, a company may elect to engage in a sale-leaseback to redeploy the proceeds into a new business initiative or assets such as equipment or human capital.

While a company may conduct a sale-leaseback for one or more of these reasons, another motivation may be to unlock value that is being consistently underappreciated, particularly in the public markets.

For example, a company may have real estate holdings that are worth a significant amount approaching or even exceeding the company’s market capitalization, which may have been depressed due to operational concerns. A sale-leaseback allows the company to receive the full market value of the real estate, which can be distributed to shareholders, allowing the company’s operations to subsequently be independently valued.

This argument was frequently made over the past decade by investors in retail chains, which suffered from falling valuations due to operational underperformance and concerns about the threat of e-commerce but retained vast real estate holdings.

Most recently, activist investors in Kohl’s (NYSE: KSS) have made sale-leasebacks a point of contention. While Kohl’s stock has declined since mid-2022 for a variety of reasons, particularly due to a decrease in consumer discretionary spending, activists believe that Kohl’s is significantly undervalued.

Kohl’s real estate, which it owns almost all of, is worth over $8bn, compared to an ~$2.8bn market cap. Led by Macellum Capital, which holds ~5% of Kohl’s, the activist group launched two proxy fights to fully replace management. Macellum argued that management’s lack of retail experience and poor leadership have contributed to the chain’s decline over the past decade.

The activist group called for a sale process or significant sale-leasebacks. However, management publicly stated that it was unilaterally opposed to engaging in sale-leasebacks, reportedly due to concerns regarding the chain’s financial health.

While a sale process gained interest from Sycamore Partners and Hudson Bay Co. before culminating in an exclusive agreement with Franchise Group Inc., management later called the agreement off due to rising interest rates and a choppy economic climate.

Ultimately, Kohl’s replaced three directors and formed a new capital allocation committee, and it seems the battle has stalled after Kohl’s management won the latest proxy contest.

In order to determine whether a sale-leaseback will unlock value, a company (or its advisors) can use valuation multiples. Specifically, the company would compare its business multiple and the capitalization rate, or cap rate. The business multiple commonly used is Enterprise Value / EBITDA, portraying the value of the business as a multiple of EBITDA, a proxy for cash flow.

Meanwhile, the cap rate is an assessment of the yield of the real estate over one year, calculated as Net Operating Income (NOI) / Asset Value. This will produce a percentage (e.g., $1mm cash flow / $20mm asset value = 5% Cap Rate). By dividing 1 by the Cap Rate (e.g., 1 / 5% = 20), you can use the cap rate to imply a valuation multiple representing the value of the real estate asset as a multiple of its cash flow.

By comparing the Enterprise Value / EBITDA multiple to the Cap Rate implied multiple that outside investors would pay for its real estate at current market prices, the company can determine whether engaging in a sale-leaseback will be accretive.

For example, if the whole business (including the real estate assets) currently trades at a 10x EV/EBITDA multiple, but an investor would be willing to pay a 12x Cap Rate implied multiple for the real estate, then executing the sale-leaseback at 12x, higher than the current business’ multiple, would likely drive immediate value creation.

Additionally, comparing the cost of capital is critical if a company would like to use a sale-leaseback to finance new initiatives or reduce leverage. In order to make sense, a sale-leaseback should be attractively priced compared to a company’s weighted average cost of capital, or WACC.

When the implied cap rate on a sale-leaseback is lower than the WACC as well as the incremental cost of debt capital, a sale-leaseback becomes appealing from a cost of capital perspective. A helpful way to think about this is through a company’s expenses.

If taking on new debt would force the company to borrow at a 10% interest rate, but a sale-leaseback could be done at a 6% cap rate (implying lease payments representing 6% of the to-be-sold asset’s value), it would make sense to pursue a sale-leaseback and pay a lower amount of rent compared to a higher amount of interest.

This could mean that sale-leasebacks make sense for certain properties with lower cap rates–since the company would be making lower lease payments once it sells the property–but not other properties with higher cap rates.

Beyond these metrics, there are several other considerations a company’s management should evaluate before engaging in a sale-leaseback. First, management should determine whether future cash flows will sufficiently cover the lease expense that will be created by the transaction.

This is often a significant annual expense that did not exist before and can put a strain on the business, particularly if cash flows decrease in the future and the initial proceeds from the transaction have already been used or distributed.

Another important consideration is the long-term strategic importance of the real estate that will be sold and subsequently leased. Since the company will be contractually obligated to lease the real estate for a minimum of 15-20 years, sale-leasebacks should only be used when management is confident that it will continue to utilize the real estate over the long term.

On the flip side, while real estate investors generally want the lessee to continue to renew the lease, depending on how the contract is structured, there is a possibility that the lessee will not be allowed to renew so that a new lessee can be brought in.

Furthermore, if the lease terms are renegotiated after 15-20 years (or 40+ years if the initial sale leaseback has built-in renewal options), the lessee could have to make higher lease payments. These potentially elevated interest payments in the future will be on top of the payments that were created by the sale-leaseback itself.

In summary, management must understand how the investor they will sell to and subsequently lease from typically operates to ensure there is proper alignment so that the business can properly function over the long term. Additionally, management needs to have confidence that future cash flows will sufficiently cover the new lease expense that was created by the sale-leaseback.

Sale-leasebacks in Private Equity / Restructuring

Given their numerous use cases, sale-leasebacks have grown in popularity, particularly over the last decade. Additionally, interest in sale-leasebacks has surged over the past year due to the tight capital market environment for corporate borrowers.

As this proliferation has occurred, sale-leasebacks have contributed to both helping companies avoid bankruptcy and fall into bankruptcy, most notably in situations that have involved private equity ownership.

One of the most controversial uses of a sale-leaseback involves a private equity sponsor having one of its portfolio companies engage in a sale-leaseback when it does not make operational sense for the business but would boost the returns of the sponsor.

This is typically undertaken almost immediately post-buyout of the portfolio company. The sponsor would have the portfolio company divest its real estate assets and subsequently lease them back, generating a significant one-time cash inflow, but forcing the company to make long-term annual lease payments. Using the one-time cash inflow, the sponsor would have the portfolio company issue a special dividend to itself, generating a significant amount of cash.

While the future lease payments will reduce future cash flows and therefore returns, the special dividend typically more than compensates for this difference, generating net positive returns to the sponsor.

Sale leasebacks have been commonly used by Sycamore Partners, a notable consumer and retail private equity firm, in its buyouts of Belk, Staples, and other companies.

The opportunity to conduct sale-leasebacks was one of the firm’s primary motivations in its 2015 acquisition of Belk, which eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2021. It is estimated that Sycamore may have completely earned back its equity investment into Belk through sale-leasebacks alone.

Another sale-leaseback conducted under a private equity sponsor that most likely contributed to bankruptcy was conducted at ManorCare, a portfolio company of Carlyle. When Carlyle acquired HCR ManorCare (now ProMedica Senior Care), an operator of assisted living facilities, ManorCare owned its real estate. In 2011, Carlyle had ManorCare engage in a $6.1bn sale-leaseback in which ManorCare sold its real estate to HCP, a REIT.

The proceeds of this transaction allowed Carlyle to completely recover its $1.3bn equity investment, with the remainder applied to debt paydown. After Medicare cut reimbursement rates in 2011, the whole industry suffered. Unlike when it previously owned its real estate, Manorcare was now also saddled with significant lease payments amounting to $472mm annually, or ~11% of revenue, set to escalate by 3.5% annually. By 2012, some of its facilities began to miss rent payments, and residents and employees began to complain about declining quality of service and understaffing.

When Manorcare eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2018, various experts and analysts concluded that Manorcare’s unsustainable capital structure, largely due to the sale-leaseback, played a major role in the company’s failure.

At the same time, sale-leasebacks have helped companies gain liquidity and avoid bankruptcy. This is something that has been seen extensively in Las Vegas, where casinos make prime sale-leaseback candidates due to their immense value and the barriers to new construction.

Apollo and TPG notably used sale-leasebacks to delay the bankruptcy of Caesars Entertainment, as well as to fund new growth initiatives. Sale leasebacks also played an important role post-2008 Great Financial Crisis, helping several companies avoid liquidity crunches (although not all were successful over the long term).

For example, YRC Worldwide, a trucking company, used sale-leasebacks to obtain over $500mm in cash in 2009, while the Times Co., the parent company of the New York Times, raised $255mm from the sale of its NYC headquarters. Other companies, such as Walgreens and Taco Bell, have continually engaged in opportunistic sale-leasebacks to raise capital for growth over decades.

Ultimately, it is likely that sale-leasebacks will continue to play an important business role. Sale leasebacks are the most effective way to immediately tap 100% of a real estate asset’s value while retaining operations; however, this comes with reduced future optionality due to lease payments and reduced control.

Given that sale-leasebacks have clear-cut benefits and drawbacks, it remains up to a company’s owner and management to determine whether a sale-leaseback is the right tool to use to accomplish its goals.